Uncertainty As A New Community Practice at the Queens Museum

September 15, 2021

Researcher Stella Toonen looks back at her experience studying the Queens Museum’s community engaged practices in 2020, and reflects upon its response to the pandemic and the Year of Uncertainty, as she’s experienced it from afar in 2021.

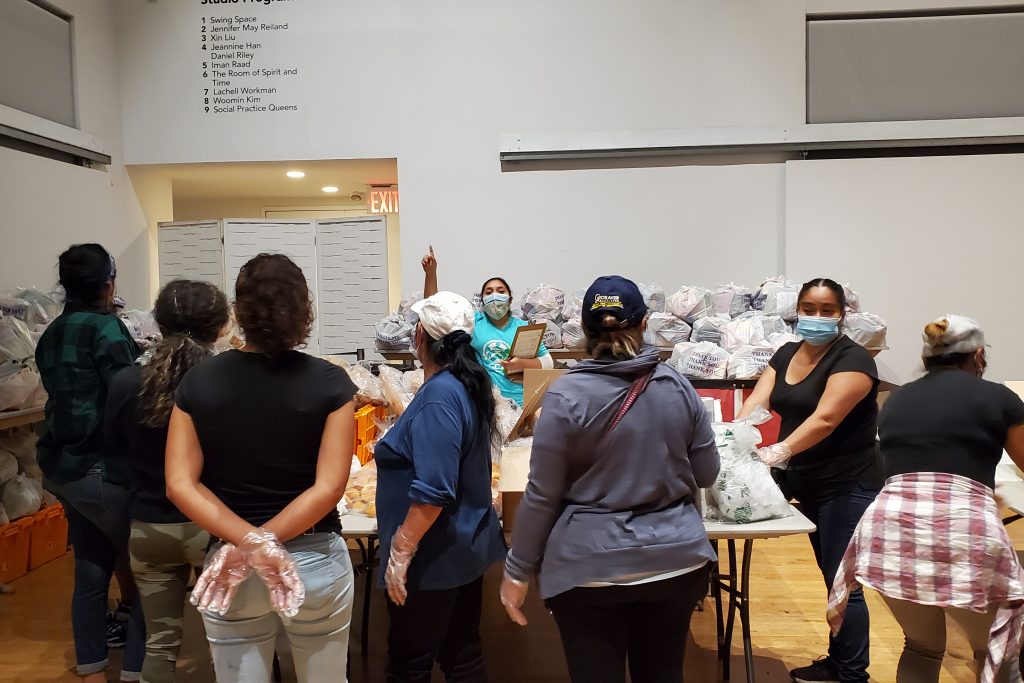

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and Queens turned out to be at the epicenter of the first virus wave in the US, one of the first things that the Queens Museum did was to ask its local community, ‘How can we be of help to you?’ And more importantly, it genuinely listened. In fact, it even has a Community Organizer on staff, someone to represent the local community within the Museum, to help answer that question. Hence, when museums all over the country were hurrying to move their exhibitions online and to develop education packs that could replace physical school visits, Queens Museum was embarking on an entirely different project to meet the needs of its community: a food bank.

The food pantry formed the start of a series of lockdown projects that were informed not by what staff wished to do, or by what museums were supposed to do, but by working closely with communities to understand their needs. It seems a simple approach, but in fact it is difficult to do well, as it requires an extremely open-minded and flexible practice that embraces the uncertainty of changing needs. To shape a more structured approach to such work and offer a way to embed new learning from it, the Queens Museum launched the Year of Uncertainty program in 2021. It invites community groups, artists, and co-thinkers into the Museum to shape and produce projects and test new ways of working. “It’s a year of learning together,” one staff member says, “and we don’t know yet what the end results are going to be, so that’s the uncertainty part.”

The Queens Museum’s response to the pandemic of building open-ended collaborations with communities is not only helping local audiences in the borough of Queens, but also giving the Museum the opportunity to try out new ways of working and create change within its walls and programs. And so I wonder if the Year of Uncertainty, for the museum, could perhaps be dubbed the Year of Change.

New Roles for Museums

To me, as a researcher of community engagement projects in museums, the food pantry project came as a refreshing example of a museum exploring new parts of its community role. Many museums might have rejected the idea for having nothing to do with art. But at the Queens Museum making art and serving the local community go well together, and this is at the core of the Year of Uncertainty too. A long history of socially engaged art projects have helped to establish ways of working in which art can be useful. It follows Tania Bruguera’s Arte Útil (‘useful art’) thinking, which has greatly influenced the Museum for over a decade, and has in the past led to hosting immigrants rights movements, local activists and social justice charities at the Museum.

Indeed, while a food pantry or a social justice program might be quite far removed from the classic notion of what a contemporary art museum looks like, a museum’s public access and mission to contribute to society actually make it quite a fitting space. It fits the wider paradigm shift that is visible in museums in the U.S. and Europe, that moves away from the historical vision of museums as temples for art towards seeing museums as forums, town halls, or public places in which communities can convene and feel included and empowered. It also promotes the idea that audiences should be able to participate more in deciding what museums should be and look like. It has led to a surge in ‘co-creation’ projects, in which community groups are heavily involved in producing exhibitions, programs, or general decision-making, as equal partners to museum teams.

The COVID-19 pandemic has offered a particularly effective opportunity for museums to rethink their relationship to audiences and communities. The lockdowns and museum closures provided a moment for museums to pause and reflect on what these groups really needed and that resulted in many new, creative approaches that challenged what roles museums could serve for their audiences and communities. These included food banks, but also marketplaces, spaces for protest, language schools, art schools, kitchens, and vaccination centers in some cases. It seems the new (post-)COVID-19 era is questioning what roles museums can play in society and the answers are inventive and wide-ranging.

Community Collaboration at the Core of the Museum

The (post-)COVID-19 era seems to be defined by an increasingly close relationship between museums and communities, but successful collaborations can be difficult to achieve. Inviting communities of non-professionals to work with museum staff makes for a constant negotiation of ideas, interests and power, and requires a carefully managed relationship between all partners involved. Moreover, only consulting the communities on what they need from their local museum space is not enough. To really embed the community into the museum, co-creation needs to happen throughout all phases of a project to ensure it can adapt to changing needs, as well as give communities agency to take ownership of the project. It requires a real commitment to a co-creative way of working, and for project structures to be set up for collaborative decision-making.

Integrating co-creation approaches into all organizational structures is not easy and it doesn’t only require time, but also buy-in from the museum’s workforce. Collaborating with audiences and communities is generally an exercise in giving away power, to create situations in which the curators and directors aren’t the sole decision-makers anymore, but instead they form part of a larger ecosystem and are accountable to the communities within it. In my research I have noticed that this is often initially met with apprehension and takes time to become standard practice, as many curators and other professional staff find it difficult to let go of their hard-won position of expertise and power. Moreover, it is often an exercise in coping with uncertainty too, where curators and program producers at the outset of a project often don’t know what the outputs are going to be, as those depend entirely on the contributions the involved communities make along the way.

The Year of Uncertainty and Organizational Change

The Queens Museum’s choice to celebrate uncertainty with a yearlong program of creative activity is a major provocation to how museums work, just like a food pantry powerfully challenges our conceptions of what museums should be. The Queens Museum is keen to use the global pandemic moment to shake up its staff, communities, partners and the world more generally, and to show them how museums might be different in a (post-)COVID-19 future. How different exactly, that is of course part of the uncertainty element of the outcomes, but director Sally Tallant highlights another, potentially more important aim: “I don’t know yet what it will prove, but by the end of the project, we should better understand how we can function as a museum.” Indeed, the program’s real potential is in bringing change to the organization and developing new ways of working more closely with communities.

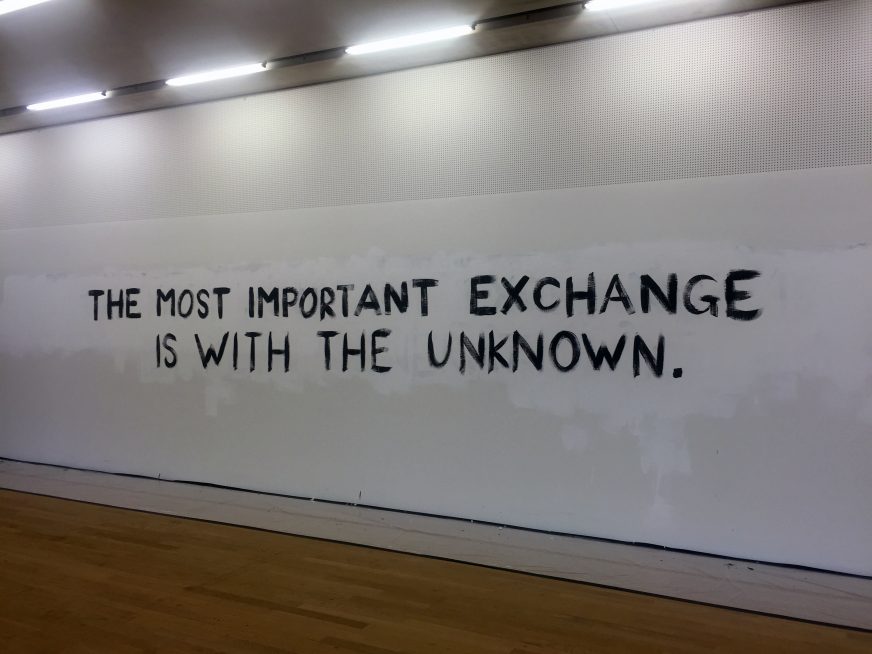

Image Description: The words “The most important exchange is with the unknown” appear in black capital letters. They are hand drawn on a long horizontal gallery wall. Below is a wooden floor, and above, neon lights.

One of its big provocations is the public embracing of uncertainty. For staff, this program is a short course in open-ended working and in letting go of expectations, hierarchies, and institutional ways of working. But a project that runs successfully without clearly defined outcomes also prompts other organizations in the sector, such as funders, to challenge their protocols and expectations. Funding structures–like evaluation, lobby and policy structures–are usually all about setting aims and objectives, determining impact and measuring outcomes, while in co-creation projects like the Year of Uncertainty much of its success lies in the process, rather than the product. The Queens Museum reconceptualizes a deeply ingrained idea of how projects should be run, and its model and example might extend well across the entire museum sector.

Another big change was already visible between the start of the food pantry in April 2020 and the launch of the Year of Uncertainty eight months later. Where the staff members I spoke to during my research described the food pantry project as “reactive”–initiated and led by La Jornada food pantry in Queens in response to an acute need–they argued the Year of Uncertainty takes a much more proactive approach: it was carefully designed by the Museum together with a group of community thinkers, a public call-out shaped the selection of partners from Queens; and the ways the partners are hosted by and embedded into the Museum have been given much consideration. It is important to take this more structured proactive approach, as one staff member explains in an interview from just before the Year of Uncertainty kicked off: “So far our work has been quite touch-and-go around needs and urgencies, but this high-level conversation about ‘What kind of relationships do we have?’ or ‘Who do we want to be in these relationships?’, that’s something we should currently be discussing.”

As a result, this careful and more consciously developed approach allows for the space and time to shape a collaboration framework between the museum and its communities. It builds deeper relationships in more equitable ways, because there is the possibility to carefully test and develop them. It avoids the risk of choices being rushed and based on practical decisions rather than tested best practice. Moreover, this approach also gives staff the possibility to bring their own skills and interests into the collaborations with communities, rather than having their work dictated by what is needed at the time. It is a change in practice that could offer many benefits to the Queens Museum more generally, and make for more impactful outputs both for the community groups and the staff members involved.

A final change that the Year of Uncertainty program might bring about is a shift in power towards the community in Queens. Asking what the neighborhood needs is an effective consultation strategy and responding to that need with a food pantry shows commitment to helping its audience. However, it expects that the users of the food bank remain mere beneficiaries, and are not in a position to have much agency over the project. Only by inviting communities into the design, creation, and decision-making processes within the Museum–as is the case in the Year of Uncertainty program–can they reach a level of authority that is equal to that of the museum staff. It creates a project that is fully inclusive and in which everyone’s voices are heard. Only then, a project becomes genuinely shared, or co-created, and usually it is exactly in that space that the most impactful learning happens for all of those involved.

Uncertainty and the Future

The next challenge for the Queens Museum will be to take the learning from the Year of Uncertainty and use it to build more fundamental institutional change across the organization that really embeds community-focused working into all elements of the Museum’s work. Working with communities is different each time–depending on the community, the locality, the timing, the personalities involved, and so on–and hence it is important to capture and retain learning from each project, so as to not have to reinvent the wheel each time. Boiling that learning down to a framework for collaborative working can help museum staff feel more comfortable sharing their agency and power, produce more impactful projects, and celebrate all of the projects’ elements of uncertainty.

While the pandemic might have felt like a threat that has sent most of the museum sector–if not the whole world–into a reactive frenzy, the Year of Uncertainty shows the crisis has also been an opportunity. If anything, it has been a moment to pause and reflect, to listen and recalibrate, to build deeper relationships, and to proactively try new ways of working. It has given museums an excuse to do things differently and to reimagine museums that are much more community-focused, flexible and collaborative, and that celebrate genuine and equitable relationships with its audiences and communities.

Related Tags